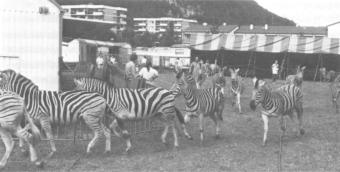

Fig. 1. Not all circuses are large. A,small circus encampment touring the village greens, with a llama, a couple of ponies and dogs, a clown and trapeze artistes. The people and the animals have a variety of acts and chores.

Chapter 2

About Circuses

Circuses come and go overnight in city parks, town market places and village greens. The circus is not only a moving theatre which provides its own building, sets, seats, lights, generators, actors (some of whom are of different species), but also living accommodation, kitchens and food for all the different species. By contrast, professional human theatres often find it difficult to even build the sets and operate the lights, never mind constructing the building, and moving it around!

This is not the place for a sociological study of the people in circuses, but some background to how the human community and the circus as a whole works is essential in order to understand the importance, role and treatment of the other species within it.

Anyone in the circus will help with any job that needs doing within their capacity, and there are jobs for toddlers and grannies. There are of course squabbles within the circus community, as in families, but the unity and cooperation towards a common goal of the people in the circus is something that is not often seen elsewhere. Children grow up learning their chosen skills, of which there are many on offer: from horse trainer, to trapeze artiste or clown, electrician or mechanic, public relations officer, public speaker, or lion presenter. At the same time, they have the discipline of having to muck in and help wherever they can and are needed.

The tented circus is essentially a nomadic multi-species community. The life of all involved can be divided up into different phases:

We will describe briefly how the humans and animals live in each phase.

Fig. 1. Not all circuses are large.

A,small circus encampment touring the village greens, with a llama, a couple

of ponies and dogs, a clown and trapeze artistes. The people and the animals

have a variety of acts and chores.

The resideritial tented environment consists of the Big Top, surrounded usually in a circle by the caravans and trailers in which the humans and some of the animals reside - i.e. pet dogs, and some young animals that are being hand-reared e.g. jaguars or lion cubs, or young primates (Figure 2). The stable tents in which the the larger performing animals are kept are usually near the artists entrance to the Big Top and inside the trailer ring. In the relatively small British circuses there may be one large tent with elephants, and a variety of ungulates, and perhaps another with horses and ponies and other species. The carnivores - the big cats, bears etc. - live and are transported in custom-built trailers, known as beast wagons (Figure 3). These wagons are also within the outspan and near by. The cats have a netted runway into the ring so that they can run directly into the ring from their wagons. Netted runways afford safe and easy ways of making or allowing the big cats to move from one place to another. The exercise cages for the big cats are usually adjacent to their wagons so that they can leap down into them or run through a short netted runway.

Fig. 2. A young jaguar and lion who

are being hand reared in the rearers caravan

Fig. 3. A typical beast wagon..

The service vehicles (trailers for props, the Big Top etc.) will be parked in the surrounding ring, or within it, and other necessities such as the generator, toilets, washing facilities, any canteen etc., will also be strategically placed within the circle.

Services such as electricity and water and sometimes drainage are usually available, in Britain, by plugging into the mains on site. This is not always the case, however, and the circus has to be self-sufficient in such arrangements. Connections to each caravan and the stable tents, as well as the Big Top, are made quickly on arrival. A skip is hired or provided by the site-owner, and rubbish including animal manure is deposited in it. Not all the circuses provide proper clean toilet and washing facilities for either their own community or the public. This is an area which could and should be improved.

There is considerable competition between the circuses for sites, and areas around which they will each travel that year. The Association of Circus Proprietors was apparently first set up to avoid squabbles and clashes and to establish a fair distribution of sites to each member. This has, it seems, worked to a degree among the members, but non-members are not controlled by the same good sense, and often gazump by rushing into a good site before the scheduled circus arrives. This happens to a degree because the site-owners charge considerable sums for hire of the site and it can be attractive to let it as frequently as possible.

Inevitably, holes are made in the ground for tent poles and so on, and the elephants are prone to dig. If it is wet and the site has no hard standing, it can be churned up to a muddy mess. Not only do all the trucks with the circus paraphernalia, animals etc. have to come on to the ground, but often parking for the audiences cars is also provided.

Some councils have, under pressure from anti-circus groups, banned circuses with performing animals from their grounds. The results of this have sometimes been that the circus has found a private ground which may not have the same services. I visited two or three sites of this type which with inclement weather had turned into muddy swamps, good for neither human nor beast.

Mud is something circuses have learnt to live with over the years, and they have in general efficient strategies for cleaning the tents, animals etc. and keeping them clean, putting down hard standings, and pathways, and coping as well as possible. However, the weather in Britain frequently gets the better of them, particularly in the autumn and early spring. The circus proprietors are, in general, acutely aware of the need to keep the encampment clean and tidy in order to make a good impression on the public to whom they are on view 24 hours a day. Bad weather and the enormous amount of extra work it entails can be depressing for all involved.

Disasters do strike, for example floods throughout the circus encampment happen from time to time; but the most frequent disasters are winds blowing down and ripping the Big Top. The threat of a real gale will be almost the only occasion on which a performance will be cancelled, and the Big Top taken down.

We will now consider how and where each group of animals live in the tented circus.

| SPECIES |

TOTAL

|

performance

|

solitary

|

group

house |

beast

wagon |

exercise

yard |

individual

handling |

|

No

|

No

|

No

|

No

|

No

|

No

|

||

| Lions |

43

|

40

|

0

|

-

|

43

|

30

|

22

|

| Tigers |

58

|

57

|

1

|

57

|

58

|

35

|

10

|

| Leopards |

8

|

8

|

3

|

5

|

8

|

5

|

5

|

| Snow leopards |

5

|

1

|

-

|

5

|

5

|

5

|

4

|

| Puma |

5

|

3

|

2

|

3

|

5

|

4

|

3

|

| Jaguar |

2

|

1

|

0

|

2

|

2

|

2

|

0

|

|

Lynx

|

2

|

tr

|

1

|

0

|

1

|

0

|

1

|

| . | |||||||

| Hyena |

2

|

tr

|

-

|

2

|

2

|

0

|

0

|

| Wolves |

2

|

tr

|

-

|

2

|

2

|

0

|

0

|

| Dogs |

43

|

43

|

-

|

43

|

43

|

25

|

43

|

| Bears(black) |

7

|

4

|

3

|

4

|

7

|

5

|

-

|

| . | |||||||

| Primates | |||||||

| Rhesus Monkey |

1

|

1

|

1(H)

|

.-

|

-.

|

-.

|

.

|

| TOTAL- |

177

|

157

|

11

|

123

|

177

|

111

|

91

|

| MEAN % |

-

|

88

|

6

|

69

|

100

|

62

|

51

|

KEY H = kept with humans, tr = training

The carnivores

The carnivores are usually kept and transported in beast wagons. These are cages on wheels which can be sub-divided into sections from the outside. In this way, the cages can be cleaned and the animals can be manoeuvred from cage to ring without the handlers going into the cages. Three sides are solid metal and the fourth long side is barred, over which a metal canopy can be secured at night or during travel. The animals may be kept in adjacent sub-divisions of the beast wagons, or in one group. The number of cubic metres per individual varies between 0.17 and 4.5 for an adult lion, tiger or leopard.

They are usually fed six days a week - on heads of cattle or sheep which are easy to come by and cheap. They are given a mineral supplement as well, and watered two or three times a day. They were given between 0.5 and 3 kg per animal per day.

At the start of this study, there were many carnivores that were not out of these wagons except for the 10 minutes or so of the performances per day. This meant they were severely restricted behaviourally. However, since November 1987, the circuses in the Association of Circus Proprietors themselves have brought in inspection procedures and necessary provisions for animal welfare in the circuses (see Appendix 1). One of the provisions is that no animal should be confined to the beast wagons all the time, but must have exercise yards or rings provided. This self-imposed regulation is subject to spot checks by the circus veterinarian, or other appointed personnel.

Nevertherless, there are times when the animals do not have exercise areas available, and some animals, particularly those out of public view at winter training grounds, have access to these very little, if at all. Confining the animals to small beast wagons for all their working lives is not ethologically or ethically sound (see Chapter 9), even if they do not show high levels of distress (see Chapter 6) and it is imperative that proper exercise yards and rings are provided for ALL the carnivores at least during the hours of daylight. Some argue that if the animals are allowed into large areas to play and exercise for long periods, then they are less willing to work energetically in training or at the performance. If this is the case, and the animals will not work satisfactorily when provided with these minimal facilities, then they should not be kept.

In addition to the provision of exercise areas, much could be done with the beast wagons themselves in order to enrich the environment for the animals. For example, shelves could be provided which would allow the animals to use the third dimension, and also to climb and lie high up which leopards in particular seem to prefer. Branches, tyres, ropes, hammocks and so on could be provided in the wagons, and toys could be provided more liberally in the exercise enclosures which could be easily and quickly constructed around the wagon.

Fig. 5. Exercise runs can be attached

directly to the beast wagon so that the carnivores can go in or out at will.

Both zoos and circuses can have problems with their animals not taking enough exercise. In circuses, this can be overcome in the training and performing sessions, but if for some reason this is not possible, then certain strategies to encourage exercise, such as chasing moving objects, or searching for food, could be initiated.

Bears are also kept in beast wagons although they are often handled more and taken for walks and so on. One bear keeper had constructed a swimming pool inside the beast wagon for the bears, which they used in hot weather. However, proper exercise yards/enclosures should always be provided.

The domestic dogs are often kept inside trailers, either in groups or in individual cages and only taken out for walks twice a day and for the performance. This is an unnecessary restriction. The dogs should have proper exercise yards, possibly attached to their trailers which they can use at will. Alternatively, they can be tethered around the campsite or in one area. If they bark continuously, the solution should not be to shut them up more so that they cannot be heard, but rather to look at the cause of this persistent disquiet (often related to frustration of the dog in one way or another), and try to accommodate it. If this cannot be done and the animals cannot be trained not to bark at inappropriate times, then once again the environment is not ethologically sound and they should not be kept. Ideally, domestic dogs should be so trained and obedient that they can be left to run around the campsite without causing a problem of any sort; this is by no means impossible to achieve.

Fig. 6. Proposed improved

living accommodation for the carnivores.

The beast wagon has an extension

that is quick and easy to erect and to which the animals should have

access to, at least all day. This can open into the exercise yard or ring and

to the circus ring by netted runways. The wagonslsleeping areas should have

appropriate furniture for the species. For example, leopards should have

private boxes they can retire to at will, shelves for sleeping on, ropes and

branches to climb and use and so on.

|

Paenungulata

|

|||||||

|

SPECIE

|

TOTAL

|

Performance

|

Solitary

|

Group House

|

Tied

|

Loose Yard

|

Occasionally

Free |

|

-

|

-

|

No

|

No

|

No

|

No

|

No

|

No

|

|

Indian Elephants

|

31

|

31

|

3

|

28

|

31

|

15

|

14

|

|

African Elephants

|

5

|

5

|

1

|

4

|

5

|

5

|

5

|

|

Ungulates,

Artiodactyls

|

|||||||

| Pygmy Hippopotamus |

1

|

0

|

1

|

0

|

0

|

1

|

0

|

| Pig (domestic) |

8

|

8

|

3

|

5

|

0

|

8

|

0

|

| Reindeer |

5

|

5

|

1

|

4

|

2

|

4

|

0

|

| Eland |

1

|

1

|

1

|

&Co.

|

1

|

0

|

0

|

| Bison |

1

|

1

|

1

|

&Co.

|

1

|

0

|

0

|

| Water Buffalo |

1

|

1

|

1

|

&Co.

|

1

|

0

|

0

|

| Zebu Cattle (Bos indicus) |

1

|

1

|

1

|

&Co.

|

1

|

1

|

0

|

| Ankole Cattle (B.indicus) |

2

|

2

|

0

|

2

|

2

|

2

|

1

|

| Highland Cattle (B.taurus) |

3

|

3

|

1

|

2

|

3

|

3

|

2

|

| Goat (domestic) |

2

|

2

|

2

|

&Co.

|

2

|

2

|

1

|

| Camel (Bactrian) |

19

|

19

|

4

|

15

|

19

|

10

|

0

|

| Llama |

16

|

16

|

4

|

12

|

16

|

12

|

2

|

| Guanaco |

3

|

3

|

-

|

3

|

3

|

3

|

3

|

| Alpaca |

1

|

1

|

1

|

&Co.

|

1

|

1

|

0

|

|

Perissodactyls

|

|||||||

| Zebra (Grevys) |

1

|

1

|

1

|

&Co.

|

1

|

0

|

0

|

| Zebra (Hartmanns) |

15

|

15

|

4

|

11

|

15

|

4

|

0

|

| Mule |

3

|

3

|

1

|

2

|

3

|

1

|

2

|

| Donkey |

1

|

1

|

1

|

&Co.

|

1

|

1

|

1

|

| Pony |

49

|

49

|

2

|

47

|

24

|

22LB

|

7

|

| Horse |

75

|

75

|

20

|

52

|

30

|

45

|

4

|

|

Marsupials

|

|||||||

| Wallaby |

1

|

1

|

1

|

&Co.

|

1

|

1

|

0

|

| TOTAL |

245

|

244

|

55

|

190

|

163

|

141

|

42

|

| MEAN % |

-

|

99

|

22

|

77

|

66

|

57

|

17

|

KEY &Co = with other species, LB = loose box

In the tented circuses, the elephants are traditionally kept shackled. They are shackled by a front and a hind leg by covered chains. They stand on boards 4 metres by 3 metres. They can lie down, with difficulty, and they can move about 1 metre forwards and backwards. Each elephant has its own place. When the study began, some of the elephants were kept shackled for 24 hours, except when they were taken off for performance. This is not an ethologically acceptable way of keeping elephants since it restricts their behaviour greatly. However the Association of Circus Proprietors (ACP) brought in an edict that the elephants must be unshackled for a considerable amount of time each day, other than for performance. One of the problems is how to leave elephants outside, loose, in safe, easily erected enclosures. I suggested that it might be possible to use electric-wired enclosures, provided the elephants had some training to the electric fence, and then keep them at least for the majority of the daytime loose in groups. This was tried out by one circus in the summer of 1988 and found to be very successful; so was quickly adopted by several others.

Fig. 8. Young Indian elephants in a

European circus shackled on boards.

Fig. 9. African elephants in an electric-wired

enclosure within the circus encampment. A normal electric fence used for farm

stock can be used.

The elephants are also sometimes tethered and given objects to manipulate, or taken for walks or allowed to play about free in open ground, on the beaches, in rivers or wherever it is permitted by the local landlords and councils. One aspect of the efforts of organisations trying to ban circuses has been that they have been prevented from going down to the beach, or going for walks in certain areas (e.g. Blackpool). This has not improved their welfare.

Fig. 10. Indian elephants out for a

graze and walk with their trainer (on the bench).

There is no doubt that shackling elephants for prolonged periods is ethically and ethologically unacceptable. There are other ways in which the elephants can be kept for much of the time in circuses, and these must be insisted on for the majority of daylight hours at least. They are highly manipulative, curious and intellectually able animals which must be provided with sufficiently stimulating and interesting environments. This is not impossible to achieve in circuses, although husbandry systems must continue to change.

Elephants are social animals and should be kept, as a rule, in social matriarchal groups. Certain adult individuals which have been kept alone all their lives are not able necessarily to integrate well into elephant society, and this must be considered in recommending changes. Provided the animal has a strong emotional bond with its handler/trainer, this may be best for the animal, although the next generation should be brought up in social elephant groups.

Wild elephants feed for over 16 hours a day. Thus, when captive, elephants should have access to high-fibre food almost continuously to enable them to do this. They also often like to manipulate and strip leaves off branches, or the bark, or even make tools for scratching themselves out of pieces of stick. They are often given fruit, vegetables and bread by local greengrocers and bakers which adds variety to their diet

Figure 11. Shackled elephants in their

tent have eaten all the leaves off the branches they have been given. One has

broken the stick to a convenient size and is using it to scratch: an elementary

form of tool use.

Bull elephants have a reputation for being unpredictable and difficult to handle. However in Sri Lanka they are tamed, trained and worked alongside cows; although when in musth they must be confined [26].

There was only one bull elephant travelling with the circuses in Britain, and another in a safari park. The problem of bull elephants must be faced by circuses. In the wild, bull elephants are not necessarily always with the group [74; 27; 28].But circuses should concentrate on allowing their elephants to breed and live in family groups.

The ungulates (hoofed animals)

There was often only one member of a social species kept in the circuses we visited. This is not advisable (see Chapter 9). When there were more than one of each species, the artiodactyls (cloven-hoofed animals) were often kept in groups, in enclosures, within the stable tent. They are loose and in social groups. Although the social group may not be always appropriate for their species, they are able to perform much of the behaviour in their repertoire. They are all usually handled and can be led and taken out of the tent for walks, training and performance. However, they are not often taken out of their indoor enclosures for long periods each day. They also could have electric- fenced outdoor enclosures where they could run in groups.

Fig. 12. Proposed stable tent and enclosures

for the hoofed stock. The tent has enclosures within it where the animals can

be tied for individual attention, ration feeding and so on, but they are free

to wander in and out of the tent by using electric wired enclosures. This is

quite possible for the elephants and other species, traditionally wild or domestic.

They should live in the type of groups structure that they have evolved to live

in (e.g. pigs in family groups, elephants in matriarchal groups, horses in batchelor

groups or mares and their family groups).

Figure 13. Stalls or loose boxes with

high sides isolating the animal and cutting him off frorn the outside world

are not appropriate.

Figure 14. A tethered eland, not ideal,

because he is still restrained and is a social mammal, but better than being

confined to stalls or loose boxes in the tent all the time.

Some of the animals are kept tied in stalls. It is even more important that these animals are taken out for several hours a day, and allowed to run free if possible.

The major group among the perissodactyls (single-toed animals) is the equines; although there was a white rhinoceros in one circus I visited. The ponies are sometimes loose in or out of enclosures, and sometimes tied in stalls with little divisions. The horses were either tied in stalls, or in looseboxes (Figures 16, 17). Sometimes these looseboxes had the effect of isolating the animals more from their environments and their neighbours and it appeared from the analysis of the behavioural results that there were more behavioural problems and abnormalities in those horses compared to those in what one would think are the more restricted stalls.. No horses were kept in loose yards which is ethologically and ethicallv the most acceptable way of keeping them.

Figure 15. Ponies loose in the circus encampment.

Figure16. Stalled horses divided by

bars only.

Figure 17. Upmarket loose boxes for

some circus horses. The animals are isolated from each other and the outside

by wire mesh. For long periods of the day, there is little going on, and they

may only be taken out for training and performance, about half an hour a day.

In addition, they may be fed restricted fibre diets (as these were), thus having

nothing to eat for long periods. This type of stabling is very widespread among

horse owners. There was more evidence of distress as a result of such stabling

than in the stalls.

Since the majority of the horses in the circuses are stallions, it is concluded they cannot be run together; yet feral horses do have bachelor groups, and the practice is quite possible with high-quality domestic horses [29]. One circus proprietor is interested in trying such a system out.

The zebras were kept tied in stalls and handled much like the horses. When it is seen how these animals easily adapt and respond to this husbandry, it does seem absurd that zebras in zoos have to suffer darting and drugging before even their feet can be trimmed!

|

SPECIES

|

performance

|

solitary

|

group

house |

beast

wagon |

exercise

yard |

individual

handling |

|

No

|

No

|

No

|

No

|

No

|

No

|

|

|

Birds

|

||||||

|

Emu

|

1

|

1

|

-

|

-

|

-

|

1

|

|

Canary

|

20*

|

0

|

20

|

-

|

-

|

All

|

|

Macaw

|

40*

|

0

|

40

|

-

|

-

|

All

|

|

Pigeon

|

30*

|

0

|

30

|

-

|

-

|

All

|

|

Snakes

|

||||||

| Indian Python |

1

|

1

|

Box

|

-

|

-

|

1

|

| African Python |

1

|

1

|

Box

|

-

|

-

|

1

|

| TOTAL |

-

|

-

|

-

|

-

|

-

|

-

|

The birds were kept in trailers where they had cages and sometimes free-flying aviaries. One colony of macaws was allowed to fly freely wherever the circus was camped, and the trainer said she had never lost one! The pigeons all flew freely in the acts. The emu, however, was confined to a loosebox and did not appear to be taken out regularly at all. It should be implicit that the flying birds have facilities to fly wherever they are kept; the same, of course, applies to zoo birds.

These were kept in boxes and taken out several times a day for performances and training. They were handled a considerable amount, and did not appear to find this distressing. They were fed dead, not live, prey. We need much more information concerning snakes and details of their behaviour before we are in a position to make judgements about them.

The primates

The only primate in the circuses I visited was a young rhesus monkey which lived in a trailer with his trainer. The monkeys environment was stimulating and he had an opportunity for forming strong emotional bonds with humans - although not with other rhesus monkeys. He was young, and may possibly not integrate well with other monkeys later in life as a result. However, he had few behavioural restrictions.

Build up, pull down and transport

Build up is the construction of the camp or temporary township. Usually the circus will pull down the previous encampment after the last night performance (9-10 p.m.), pack everything up and move to the next site before dawn. They may begin to build up immediately on arrival, or they may sleep until dawn or into the morning and build up later in the morning.

Sometimes they have an evening performance on the same day, but usually there is no performance on the first day which is often Sunday or Monday. If they stay in small towns for only half a week (which they often do), then they will usually have performances six days in the week.

There is an enormous amount of co-ordinated work to be done requiring skill and efficiency in erecting the Big Top and the whole circus encampment. In Europe the Czechoslovaks were renowned particularly for their tent crews who used to be hired for the season by the bigger circuses. Because of travel restrictions, this role has been taken over to some extent by Moroccans; while Poles, in Europe, are often hired as stable hands. They may have two or three people whose main jobs are the tent and mechanics. Actually, everyone is expected to help and those that have no other job will also be ring boys - helping with the props, cleaning and changing the ring surface, erecting and taking down the big cat cages, leading on the animals, cleaning the Big Top, driving and so on.

The pull down and build up of the encampment and the speed and efficiency with which it can be done is a matter of pride within each circus. There is no denying how hard circus people work, nor their long hours. It is often said that good grooms are difficult to come by because so few people want to work the hours. Nevertheless, there are considerable possibilities within the circus world for those who start at the bottom of the circus hierarchy as ring boys or grooms to work their way up within a few years to be artistes, performers, animal trainers or business people within the circus. The financial rewards are not great in Britain, except possibly for a few proprietors, but there is a constant stream of people entering the circus world and remaining within it for reasons other than financial gain. The most important of these seems to be the close-knit community that the circus offers - a way of life (see Chapter 8). The great majority of those that have been born and raised in the circus stay within it, moving perhaps from circus to circus and country to country.

The welfare of animals in transport between, for example, farm and slaughter house is the subject of much concern, and it is evident that the frequent transport of circus animals should be investigated carefully.

There is a major point of difference between the transporting of unhandled naive animals from the farm and the transport of circus animals: the circus animals (similar to some competitive horses) become very familiar with being transported. Unlike the naive animals, where the whole experience appears to be distressing and the animals show physiological signs of stress (including increase in heart rate), the animal familiar with the transport and in a transporter which is relatively comfortable does not appear to find it a distressing experience

We need to do further work in this regard: monitoring heart rates would be relatively easy with the new technology. However, we monitored loading and unloading, and some animals in transport, taking pulse rates at random and found little behavioural evidence of distress.

One measure of whether animals have found particular experiences distressing is that they show unwillingness to enter the area again. Refusing to load is one of the most common behavioural problems in horses.

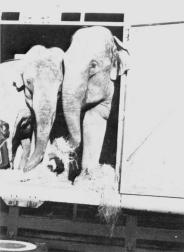

Figure 19. Elephants

in their transporter. Note the pedestal to front left which they had clirnbed

on to enter.

.

Figure 20. Loading zero-handled elephants at a zoo. A circus

crew had been hired, and the elephants had to be chained to a tractor with the

chain running through the transporter. It took four hours to load these animals.

To our surprise we found no sign of any of the circus animals not walking in willingly to the transporters. The only exceptions were inexperienced, newly acquired animals. The elephants sometimes had to climb on to pedestals in order to get into the box, and stood quietly inside with the doors open (Fig. 19). This was contrasted with the extraordinary problems we witnessed at a zoo (Fig. 20) where they were trying to load their zero handled, unfamiliar elephants. Here the elephant had to be shackled to a tractor with the chain running through the transporter in order to help pull them in! This was a dangerous operation for both the elephants and the handlers. It was interesting to see that despite the generally derogatory attitude of zoos to circuses [9), they had had to hire circus people to help with the loading.

The circus transporters varied from luxurious custom-built boxes to adapted lorries. The animals had their own familiar places in the transporter. Some travelled with padded partitions; others such as the elephants and some of the cloven-hoofed animals, without. The ungulates were usually tied individually and travelled across rather than head to the engine. Although the most common way of transporting horses, head to the engine has been shown to be inappropriate [32]. The big cats and carnivores were usually confined to individual pens in the beast wagon for transportabon.

It has been suggested that the animals might get cold during transport. The transporters, although ventilated, were enclosed and during the summer when the animals were usually transported around, it is over-heating rather than the cold that has to be considered carefully, particularly when the vehicles are still. Improved adjustable ventilators and windows which would allow some light in and allow animals to see out are necessary improvements.

For all the carnivores and some of the ungulates, the transporter was also used as the animals sleeping quarters which of course increased familiarity with it.

Travelling on minor bendy roads tends to be more tiring for the animals than on motorways where horses, for example, will rest one leg and eat and drink as they travel, once they are experienced. Although we were unable to travel with the circus animals, on arrival they were found to have eaten and there was no evidence that they had been traumatised (e.g. dried sweat, injuries etc.).

Pull down (of the circus camp) usually takes place after the evening performance. The animals are then boxed up and moved on to the next site. Before they are released from the transporters, the stable tent has to be erected - a job for the grooms. As a result, the animals may be confined to the transporter until the following midday, a period of 10 or 12 hours. They usually have access to food, and are given water on arrival at the new site, but the main objection to the transportation of circus animals on welfare grounds is that they are often confined for long periods. Recently, with the introduction of the electric pens for the elephants, the time in the transporter has been reduced for these animals. The construction on arrival of pens for the other hoofed stock would be an improvement. Similarly, the exercise yards for the carnivores should be constructed immediately on arrival in order to reduce the period in confinement.

There was no evidence to suggest that the transporting of circus animals is necessarily, or even usually, distressing or traumatic for the animals - although it is for naive farm livestock.

The performance involved the animals being exposed to bright flashing lights, noise, people, flapping tents, explosions and all other manner of sudden and what one might consider frightening stimuli. Going into the ring for a naive animal is indeed a frightening experience, as it is for a naive human being. Of necessity, the animals have to be conditioned, or trained to be able to cope with such environments. The accustoming of the animals to the ring and performances takes months and sometimes years. First, the animals are brought into the Big Top when no one is there and walked round the ring. After some weeks, when they are accustomed to this, they will begin their training. During training, they may well be brought into the ring during actual performances, and introduced to loud noises, applauding humans, flapping tents, music and clowning.

One measure of whether or not the animals found the performances distressing was if there was any resistance to entering the ring. This was not the case with almost any of the hoofed stock and elephants, some of which were apparently keen to get into the ring for performance. However, some of the big cats did have to be encouraged to leave their trailers and enter the runway to the ring by poking a broom handle into their wagon. This was more often the case for the younger, less experienced cats; approximately 40% of the animals had to be encouraged in this way.

In some cases - for example, dogs, mules, chimpanzees, some elephants and horses - there is evidence that the more experienced animals were responding to the audience appreciation. This took the form of repeating actions that had caused applause or audience response, even in the case of a group of llamas and guanacos inventing actions, such as rolling and leaping over the ring wall and back (see Chapter 6).

Figure 21. A troupe of young African

elephants walking without coercion into the ring.

Figure 22. A group of zebras running to the ring for performance,

apparently without coercion.

Circus animals have become familiar with many things that inexperienced animals would find distressing because of their past experience, lifestyle and training. The relative naivety of even animals that have been trained to be used to noises was illustrated on one occasion when some mounted police officers on experienced police horses rode past the circus encampment in a London park. There were camels, ponies, Friesian stallions and llamas tethered around the tents which were flapping, and the band was playing in the Big Top. The police horses tensed up as they approached and when they saw the animals they leaped about and took off. It took half an hour for the police officers to encourage the horses to come back past the encampment, while the tethered circus animals were eating in a relaxed way. This shows that although the police horses had been well accustomed to certain types of noise and sudden visual stimuli, their experiences had been relatively limited when compared to those of the circus animals. Therefore the police horses found the circus a frightening experience.

There is little evidence that most of the experienced circus animals find the performances distressing. Training or educating them to enter the ring willingly is all important here.

The winter quarters and static training grounds

Almost all the circuses have a farm or smallholding where they keep the stock not presently travelling with the circus, and where they go for the short winter period. In addition, two British circus businesses do not travel, but are professional sedentary training establishments. They supply animals for travelling circuses, galas, television, advertising, films and so on.

The same criticisms of the keeping conditions for the animals can be made of the winter quarters and sedentary circuses. Perhaps because these areas are not on show to the public, they may not be run very efficiently. Also, since they are where all the tent and truck maintenance is done, they can be very messy places.

The animals are not on public view and proprietors may be lax about ensuring that the animals have their exercise yards and cages and that they are well handled.

The winter quarters should be the annual holiday for the humans and the performing animals, when they can move freely, breed, relax, rest and perform some of the behaviours that may have been restricted during the season. They can also continue to learn new acts, meet new individuals who are to join the travelling show for the next season and generally recuperate.

There is usually sufficient land to be able to run many of the animals out in larger paddocks, or enclosures. However, good use of the land is not usually made, and often the animals are confined in buildings, which may be of very low quality, for the entire time. Some training is carried out in a structured way when the animals are in their winter quarters, but this is not true in all circuses

Improvements in land, buildings, land use and running of many of the winter quarters are necessary, and the same criteria of animal husbandry should be applied as in the tented shows.

The circus people are not, nor do they pretend to be, land managers or farmers; but they could and should draw on available expertise for the proper management of their winter quarters and static training areas. They often argue that the animals must continue to be housed all the time because:

The first part of this argument is often invalid. Even species which originated in the tropics can often adapt well to low temperatures, as we see in many zoos. With careful design and available housing which they can go into at will, the proper management for such animals is possible and is certainly desirable.

Secondly, if the animals have to be confined in order to be trained, then the training must be seriously questioned - and maybe either the trainer or the training should be changed. It is not difficult to train animals to come in from the field when called, and after all the circus trainers should be able to train their animals to do things that will be useful to management as well as to do tricks for performance!

During the off-season, when the circus retired to its winter quarters, the humans often depart for their holidays, prepare to join other circuses, or even turn to other businesses. One of the interesting features is that although there is frequently a house at the winter quarters, rarely does even the proprietor move into it. The house is usually used for storage and the people continue to live in their trailers which are, of course, their homes.

|

Any

non working links, comments or suggestions please contact the webmaster:

johneaston@diddly.co.uk |

|